National Association for the Practice of Anthropology

MEET NAPA’s 2019 VOLUNTEER OF THE YEAR: Brandon Meyer

NAPA recently conducted an online interview with Brandon Meyer, the designer of the new NAPA website, and NAPA’s 2019 Volunteer of the Year Awardee for the November 2019 issue of NAPA Notes:

How did you get your start in anthropology?

So I started out as a multimedia design major in college before transferring to anthropology and I only really learned about anthropology while researching for my personal blog at the time, projectdesignportfolio.com. I created that blog to dive deeper into design theory, research, and practice then I really felt I was getting at design school. That led up to my realization that what I really wanted to do was practice-based design research, which eventually resulted in my decision to change my major to anthropology in order to gain a solid research background from the start.

Even so, I maintained my interest in design and continued to take as many design classes and job opportunities as I could throughout my studies as an anthropology major. So I guess it’s no small wonder how I came about to build the new NAPA website!

What drew you to the field?

Design Anthropology – and a diverse family background of Native American, Mesoamerican, and German/Irish ancestry as well. I first read about Design Anthropology in Adam Drazin’s chapter, “Design Anthropology: Working on, with, and for Digital Technologies” in the book, Digital Anthropology. Although I didn’t decide to take the plunge and transfer to an anthropology program until I read the book, Design Anthropology: Theory and Practice.

That book and the form and direction of design anthropology that it advocates for really validated the things that I was thinking about and I never realized that these ideas were being actively developed at a much higher level than I had previously comprehended. I saw Design Anthropology as a project for an entirely new epistemology of design, with a critical mass of new design theory and a new way of practicing design that is fully aware of the responsibility that comes with being a world-building activity. I really wanted to be a part of that and so I transferred to an anthropology program and committed myself to the fringes of emerging design anthropology theory and practice (especially works post-2012).

Where did you go to school?

I went to The Academy of Art University and then transferred to North Carolina State University for my BA in anthropology. I also spent a semester at UNT’s Master’s of Applied Anthropology program.

What degrees did you earn and when?

Ultimately, I earned my BA in anthropology in 2017 from NC State, graduating there Summa Cum Laude and with honors.

What have you been doing since graduation?

Since building the new website for NAPA as a student volunteer I have been offered a paid position at the National Association for the Practice of Anthropology as a technical coordinator and blogger – and to this I credit my brief time at UNT for the opportunity to work with NAPA in the first place. I still take on work as a web and graphic designer too when an opportunity arises but I’m not serious about becoming a full-time designer. Of course web and graphic design skills are professionally relevant to me and I try to keep practiced and up to date on the latest developments, but I view them as serving a supporting role to my larger objective towards design research. Which I guess is really only saying that I believe practice-based design research is much more inclusive and expansive than design has traditionally been practiced.

I continue to advocate for experimental design research practices and alternative epistemologies of design(ing). As part of that effort, I manage the design anthropology groups on the Open Anthropology Cooperative and on LinkedIn, as well as participate in the Speculative Futures Initiative community and the Pluriversal Design SIG of the Design Research Society. That has really allowed me to grow my network and have some level of influence. I have contributed materials and commentary to the design anthropology entry written by Christine Miller and Elizabeth Briody in the upcoming Oxford Research Encyclopedia and the new Anthropology+Design graduate course taught by Shannon Mattern at the New School for Social Research. I am now currently working on a new online project that is meant to greatly facilitate collaborative anthropology projects and promote the full diversity of anthropological theory and practice.

Some design pieces by Brandon:

How have you seen your career moving along?

Honestly, while I built the new NAPA website as a student volunteer I am very happy to have been given the opportunity to stay on as the technical coordinator/web designer because it has allowed me to utilize my skills in web and graphic design while staying “plugged-in” to anthropology as both a field and a community. I’ve worked “just as” a web designer and “just as” a graphic designer and I was never really as fulfilled as I am when I am able to maintain some connection to anthropology. Saying that though, I don’t know how fulfilled I would be if I was just doing ethnographic fieldwork and not maintaining some role as a designer either! I am most happy sitting somewhere between a full-blown designer and a full-blown anthropologist…

What personal and career passions does anthropology enable you to pursue?

Although many designers may not realize it, I don’t consider it an irony that my foundational education in anthropology prepared me much more for design research than a studio-based design pedagogy ever could have. It was a tough decision for me at the time but having a background in anthropological theory and practice has served as a great foundation for the exploration of design research. Not just in terms of UX and user research as is often the area advocated for within applied anthropology circles (at the other end of the spectrum), but also in the development and critical analysis of new and experimental forms of design epistemologies, theories, research, and practices as culturally, socially, environmentally, and politically implicated world-building activities.

I believe that it is no accident that design anthropology has served as a conduit for many diverse and emerging epistemologies within design and it is exactly in those periods of volatility and transition when critical thinking, rigorous debate, and an openness to exploration is most required. Many design anthropologists have taken on that role and made valuable contributions to design that no serious design scholar could now ignore. Albeit there is still a space between the two fields as they are traditionally taught and predominantly practiced, I see Design Anthropology as a transdisciplinary space that has sought to bridge those gaps into a single practice and that’s what I’ve always focused on.

How does an “aspiring design anthropologist” navigate the professional landscape?

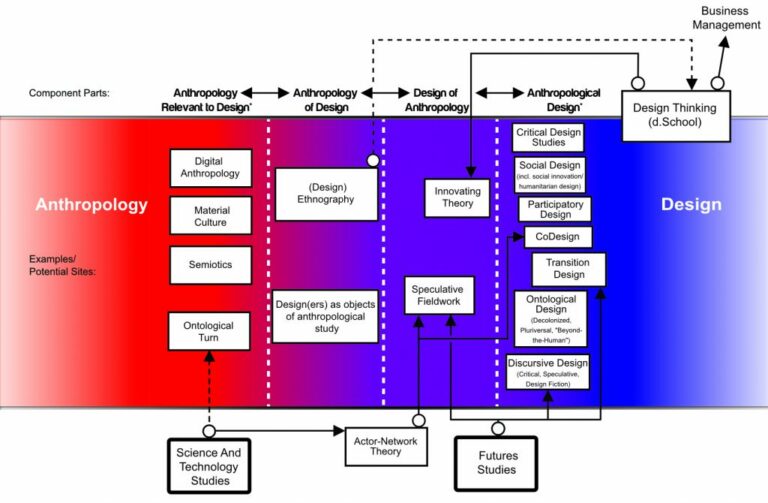

As I’ve actively followed the development of design anthropology across the “of,” “with,” “for” spectrum between the two fields – and beyond – my own professional aspirations have dramatically shifted from a designer wanting to dabble in anthropological theory and practice, to an anthropologist wanting to make an impact as such in design, to a design researcher seeking to contribute to the development of emerging areas within the field of design and anthropology through this time of transition.

So there is lots of opportunities to work within business and design but within a very limited sense. There is a standard set of “best practices” and a limited scope within industry that is necessary to fully jump on board with or to first mold any proposed practice into – this is the source of Design Thinking’s success. Many other kinds of emerging and alternative forms of design practice, like speculative design for instance, are experiencing an uphill battle as radical forms of design that exist outside of the realm of business and are either struggling to find a ground outside of academia and museums, or are undergoing a process of streamlined adaptation and commodification similar to that which the ethnographic method has undergone in business and design.

I’ve been lucky to have the opportunity to choose – not between academia or business – but between maintaining my connection with design as an experimental and theoretically-rich mode of production, and conducting more established forms of design research as a service for business. Maintaining my role as a designer has allowed me to stay close to what had originally inspired me to move into design research in the first place and to stay up to date with new and exciting forms of theory and practice within design – and mind you on a very strong footing due to my anthropological training!

Who inspires you and how does it influence your research and professional inquiry?

I have most recently been inspired by Arturo Escobar’s commentary and contributions to design that have resulted in Pluriversal Design as an emerging field of design research and practice, as well as the development of new forms of inventive methods, speculative research, and design experiments within the broader social sciences (see Lury & Wakeford, Marres et al., and Savransky et al.). So I view many emerging, critical, and alternative areas within design as part of a larger ecosystem where new epistemologies of design are interacting, commingling, and diverging across design and other disciplines. Pluriversal Design emerges in part out of Transition movements, particularly in the global south for Escobar, and the work being done in the development of the field of Transition Design at Carnegie Mellon University. Developments within decolonized design and design “beyond-the-human,” or Ontological Design, are arguably associated or derived from related or expanded concerns.

There is no shortage of design anthropologists working with, for, and beyond all of these areas, which is why I view design anthropology as a significant focal point. Having said that, much of this is centered around an overarching concern of human-caused climate change and what the future will hold that both implicates and challenges design and Western models of the world more broadly. The anthropocentric source of all of these issues makes anthropology an inevitable source of inquiry. For instance, I also argue that a critical mass of leading design researchers are taking on anthropological-lines of inquiry within these emerging design movements such as Tony Fry, Cameron Tonkinwise, Tristan Schultz, Alex Wilkie, Ahmed Ansari, and many others.

Great papers are consistently published in design journals that I consider required reading for any aspiring design anthropologist, like the Journal of CoDesign, Diseña, the Strategic Design Research Journal, Design Issues, and the Journal of Design & Culture (see my design anthropology recommended reading list). Many design research conferences are a must for design anthropologists as well, like the Papanek Symposium, the Design Research for Change Symposium, the New Experimental Research in Design Conference, the Research Through Design (RTD) Conference, the Participatory Design Conference, and the Nordic Design Research Conference (Nordes).

Brandon’s chart mapping Design Anthropology as a transdisciplinary epistemological construct.

What advice would you give to a student starting their career in anthropology?

I can offer my perspective to aspiring design anthropologists in particular. As I have written before, the mantle and traditional role of anthropologists in design has been to serve as cultural interlocutors that can inform design through ethnography, but if craft works by opportunistically pursuing moments of cultural breakdown and uncertainty in order to reframe what exists, culture itself is informed through the performance of designing. Therefore, anthropology’s productive role and epistemological purview within design can and should extend to the event of the design process. Smith and Otto explain in Design Anthropological Futures that design anthropology “represent[s] a shift from predictability in the design practice and taxonomical understandings of culture towards the enabling and becoming of potential futures and of situated future making that can be negotiated and performed through socio-material processes of design anthropological intervention” (2016:27).

Whether or not it can be said that it has achieved its claim as a distinct field, Design Anthropology is an attempt to amplify the commonalities between the two fields of design and anthropology and resolve their disconnections by extending the theoretical trajectories of the field of anthropology into the future through design by conceiving of participatory, speculative, and critical design events together as a pliant, actuating field site for (design) anthropological inquiries.

Fortunately, as a transdisciplinary, collaborative (yet still contested) field, the seemingly wide diversity of research and practice within design consistently cluster as a design anthropological discourse and any serious study of this field will more then prepare you to become a real thought leader in these emerging fields of design. While there are very few books and programs on design anthropology specifically, a lot of work is being done that falls within its purview at the cutting edge of design research today that serious students of design anthropology will instantly recognize even as they are formulated within design – referring back to the trajectory of my own shifting aspirations within anthropology “as a” designer, then in design “as an” anthropologist, and finally as a “design anthropologist,” traditional silos are rendered almost meaningless within transdisciplinary spaces and you begin to see working hybrids from every direction. While these orientations are rarely ever perceived within the established professions, there are still different ways to orient yourself between the two fields of design and anthropology depending on your strengths and interests, but despite these differences you really can go as far as you want within each. The challenge is only to get there!